Elizabeth Dudley, Countess of Löwenstein

Elizabeth Dudley | |

|---|---|

| Countess of Löwenstein | |

| Died | 1662 London, England |

| Spouse(s) | Johann Kasimir, Count of Löwenstein-Scharffeneck |

| Father | John Dudley |

| Mother | Elizabeth Whorwood |

| Occupation | Lady-in-Waiting to Elizabeth Stuart, Queen of Bohemia |

Elizabeth Dudley, Countess of Löwenstein (fl. 1613–1662), was a Maid of Honour and lady in waiting to Elizabeth Stuart, Queen of Bohemia.

Family background

[edit]

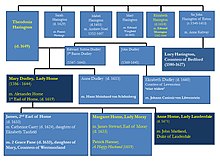

Elizabeth Dudley was probably a daughter of John Dudley (1569-1645) and Elizabeth Whorwood. The Sutton family used their title "Dudley" as a surname. A "John Dudley" who features in the diary of Lady Anne Clifford, may have been a son of Edward Sutton, 5th Baron Dudley and his mistress Elizabeth Tomlinson.[1]

Theodosia Harington wrote that Elizabeth Dudley was her niece. Harington was the mother of Anne (Dudley) Sutton, who was placed in the household of Princess Elizabeth.[2] Elizabeth Dudley was possibly chosen to join the household through these family connections.[3]

In 1637 and 1641, Elizabeth Dudley wrote letters to Ferdinando Fairfax, 2nd Lord Fairfax of Cameron about his son Charles Fairfax, and addressed Fairfax as "father" and signed herself "daughter". These were conventional signs of affections.[4]

Elizabeth Dudley appears in a list of April 1613 of those going to Heidelberg.[5] Elizabeth's female attendants on her arrival at Vlissingen on 29 April 1613 were listed as the Countess of Arundel, Lady Harington, Lady Cecil, Mistress Anne Dudley, Mistress Elizabeth Dudley, Mistress Apsley, and Mistress (Mary) Mayerne.[6]

Countess and Widow

[edit]In 1622 Elizabeth Dudley married Johann Kasimir, Count of Löwenstein-Scharffeneck, but he died later in the year. He and her cousin Elizabeth's husband Hans Meinhard von Schönberg had attended the funeral of Prince Henry in 1612.[7] Johann Kasimir drowned in the River Main at Höchst in June 1620 alongside hundreds of soldiers.[8]

In her letters the queen referred to the countess as her "Wise Widow", "Dutch Bess Dudly", "my reverend Countess", or "Dulcinea".[9] Löwenstein's correspondents in 1622 include the Count de la Tour or Baron de Tour.[10]

In 1625 a tour of North Holland by Elizabeth of Bohemia and Amalia van Solms was described in a letter,[11] probably written by Margaret Croft. The countess was at the centre of several comic incidents.[12] In 1637 Croft told a story in London that Dudley had boxed the ears of Elisabeth of the Palatinate in front of twenty people in the garden of the Prince of Orange.[13]

Another comic piece in French features Löwenstein; "The faithful and true record of the acts, progresses, and skill of the Countess of Levenstein, as ambassador of the Queen, during her stay at Breda", she was not an accredited ambassador, and the jokes revolve around her food, facial expressions, and occasional use of German phrases.[14]

The Countess travelled to England, apparently to raise support and funds for the Palatinate cause.[15] John Penington noted her as his passenger in the Convertine to the Brill Road with Lord and Lady Strange and her brother, the "Count Delavoall", Frédéric de La Trémoille, Count de Laval, in April 1631.[16]

In 1639, after staying in Bertie House in Lincoln's Inn Fields, she returned to The Hague in Pennington's ship with Lady Strange, "a good ship, excellent company, a fair wind, for one that wished herself at the Hague".[17] She corresponded with Constantijn Huygens, joking that he was a "witch", mentioning that Lady Stafford was sending a theorbo, and writing;

"In England there is nothing spoken of but the troublesome war which is like to be with Scotland, and without the great mercie of God it will be the ruin of both the kingdoms: those officers his Highness hath lent the King, which every body says his Majesty takes very kindly, will find the difference in the order of the wars in Flanders and the disorder there"[18]

She continued the "witch" theme in their correspondence, signing off, "I am confident your witchcraft cannot make me esteem (you) more than I do your merits", while Huygens played along in French and became "le sorcier". In another letter of 1639 she reminded Huygens of his old affection for Lady Stafford, in London 17 years earlier.[19]

An English soldier, Captain and then Colonel of the Anglo-Dutch Brigade, Sir Ferdinando Knightly from Fawsley appears in Dudley's letters of 1640, and had some kind of relationship with her. In 1644 Huygens wrote to Knightly that his recent promotion to Colonel at "Bergen op Zoom" would soften the widowed countess's "white marble into warm wax".[20]

She wrote from the Hague to Lady Frances Broughton, a former lady in waiting, and her husband Sir Edward Broughton at Marchwiel Hall near Wrexham, with news of their son, and assured them that Elizabeth of Bohemia "will never doubt the affection of the worthy Welsh men for she knows they are honest and Brave Men".[21]

When Elizabeth of Bohemia died in London in 1662, she arranged the queen's possessions for probate and secured some jewels and goods to cover money she had lent over the years.[22] She returned to the Hague where Marmaduke Rawdon an antiquary from York saw her and "her nieces", acquaintances of his party.[23]

References

[edit]- ^ Jessica L. Malay, Anne Clifford's Autobiographical Writing, 1590-1676 (Manchester, 2018), p. 81.

- ^ 'Will of The Honorable Lady Theodosia Dudley of Norwich, Norfolk', TNA PROB 11/215/234.

- ^ Marilyn M. Brown & Michael Pearce, 'The Gardens of Moray House, Edinburgh', Garden History 47:1 (2019), p. 5.

- ^ Robert Bell, Fairfax Correspondence, vol. 1 (London, 1849), p. 321; vol. 2, p. 196, now British Library.

- ^ Mary Anne Everett Green, Elizabeth Electress Palatine and Queen of Bohemia (London, 1909), p. 415.

- ^ Edmund Howes, Annales, or Generall Chronicle of England(London, 1615), p. 919.

- ^ Thomas Birch, Life of Prince Henry (London, 1760), pp. 525, 529.

- ^ Nadine Akkerman, Elizabeth Stuart, Queen of Hearts (Oxford, 2021), pp. 173-4.

- ^ Nadine Akkerman, The Correspondence of Elizabeth Stuart Queen of Bohemia, vol. 2 (Oxford, 2011), pp. 799, 802, 1119; vol. 1 (Oxford, 2015), pp. 159-60: Lisa Jardine, Temptation in the Archives (UCL: London, 2015), pp. 12-14.

- ^ Samuel Richardson, The Negotiations of Sir Thomas Roe, vol. 1 (London, 1740), p. 122.

- ^ Nadine Akkerman, Elizabeth Stuart, Queen of Hearts (Oxford, 2021), p. 229.

- ^ The French text is printed in Martin Royalton-Kisch, Adriaen Van de Venne's Album: In the Department of Prints and Drawings in the British Museum (London, 1988), and with an English translation in Lisa Jardine, Temptation in the Archive (London, 2015), pp. 108-119.

- ^ Nadine Akkerman, The Correspondence of Elizabeth Stuart Queen of Bohemia, vol. 2 (Oxford, 2011), p. 605.

- ^ George Bromley, A Collection of Original Royal Letters (London, 1787), pp. 271-7

- ^ Calendar State Papers Venice: 1626-1628, vol. 20 (London, 1914), p. 88 nos. 104, 449: Calendar State Papers Venice: 1636-1639, vol. 24 (London, 1923), p. 422 no. 452.

- ^ HMC 10th Report Appendix part 4 (Muncaster) (London, 1885), pp. 275-6

- ^ CSP Domestic Charles I: 1639-1640, vol. 15 (London, 1877), p. 537 and see BL Add MS 30797 ff. 11-13, and Add MS 15093 ff. 119-122.

- ^ A Catalogue of an Invaluable and Highly Interesting Collection of Unpublished Manuscript Documents, Sold By Mr Sotheby, vol. 9 (London, 1825), p. 102 lot 448 (not dated), now in the British Library Add MS 15093 ff.119-122 at f.119v, and see Add MS 18979 f.62, Add MS 30797 ff.11-14.

- ^ Lisa Jardine, Temptation in the Archives (UCL: London, 2015), p.50.

- ^ A. Worp (ed.), De Briefwisseling van Constantijn Huygens, Deel IV, 1644-1649 (The Hague, 1915), pp. 91-92, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, KA 48, fol. 49.

- ^ Cedric Clive Brown, Friendship and Its Discourses in the Seventeenth Century (Oxford, 2016), p. 75 & fn. 21: See British Library Add MS 30797 f.25., 24 February.

- ^ Lisa Jardine, Temptation in the Archives (UCL: London, 2015), pp. 14-5.

- ^ Robert Davies, The Life of Marmaduke Rawdon of York (Camden Society, London, 1863), p. 106.

External links

[edit]- Lisa Jardine, Temptation in the Archive (UCL: London, 2015).

- Seven of Elizabeth Dudley's letters to Huygens, catalogued by EMLO.

- Dudley's letters to Huygens, Briefwisseling van Constantijn Huygens 1607-1687.

- BLKÖ: Löwenstein, Johann Kasimir, Graf.

- Record of a dispute over the property of Gräfin Elisabeth zu Löwenstein, Landesarchiv Baden-Württemberg.